Chocolate’s climate crisis

This Halloween, expect to pay more for your favorite chocolate bar. Tariffs are playing a role in the price increase, yes, but there’s another force at work, far from the candy aisles of North America and Europe—in the tropics, where nearly all the world’s cocoa is grown.

Over the past two years, cocoa production has plunged as much as 40%, with prices soaring to levels not seen since the 1970s. While many blame aging trees, smuggling, or illegal gold mining, our research suggests that the primary culprit is rainfall extremes—excessive rainfall and droughts.

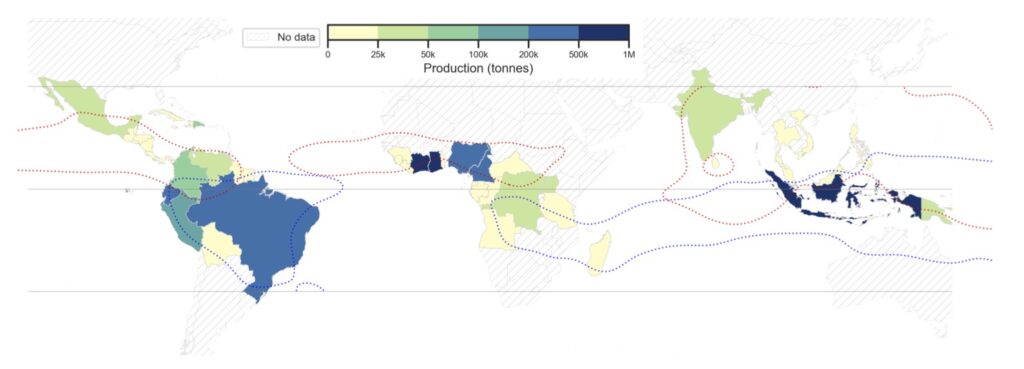

Nearly all cocoa (Theobroma cacao) is produced in the humid tropics where warm temperatures and ample rainfall alternate with short dry seasons. Four countries dominate supply: Côte d’Ivoire (≈40% of global output), Ghana (≈20%), Indonesia (≈12%), and Ecuador (≈7%). These rain-fed crops depend on the seasonal migration of a shifting band of clouds known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which dictates tropical rainfall patterns.

A price surge from West Africa

In 2024, cocoa futures surged from about $2,500 to more than $10,000 per metric ton. The spike followed years of shrinking harvests that had already strained global inventories. In 2023 Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire saw excessively heavy rainfall from April to June, followed by a harsh dry spell between November and February 2024—two extremes that rarely occur in the same year. The result: record-low yields and global supply shortages.

There is a saying in Accra: “Ghana is cocoa.” The Ghana Cocoa Board, which regulates and supports the industry, has maintained detailed district-level records of production for decades. Our team analyzed these data alongside daily rainfall and temperature observations between 2000 and 2024.

The result was striking: 68% of year-to-year variation in Ghanaian cocoa yields could be explained by wet-season excessive rainfall and dry-season drought, a remarkably high figure for any agricultural system. The relationship was geographically coherent. In Ghana’s wetter south, too much rain led to disease outbreaks and reduced yields, while in the drier northern transition zone, lack of rain was the limiting factor.

This pattern reflects a delicate ecological balance. Cocoa trees thrive on consistent moisture but suffer when rainfall becomes excessive. Heavy downpours can knock off cocoa flowers and foster fungal diseases such as Phytophthora black pod rot. On the other hand, prolonged drought as the beans develop inside the pods reduces yield and quality. The crop’s ideal conditions lie in a narrow window—one that climate change could narrow further.

Looking across the tropics

To test whether this relationship holds beyond West Africa, we extended the analysis to Indonesia and Ecuador, the next largest cocoa producers. Using national yield data from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization and similar environmental datasets, we built similar statistical models that adjusted for local rainy and harvest seasons. The conclusion was consistent: Excessive rainfall during the wet season explained much of the interannual variation in cocoa yields.

These weather shocks have major implications for the 5 million smallholder farmers that grow most of the world’s chocolate. Most of these farmers already live below a living income threshold, and greater climatic volatility threatens to deepen their financial precarity. For multinational chocolate companies, meanwhile, production shocks translate into supply shortages, higher costs, and price volatility that eventually reach consumers.

Several strategies can make cocoa cultivation more resilient to climate extremes, including agroforestry systems, varieties with greater resistance to fungal diseases, and improved water management such as small-scale irrigation and mulching. Improved forecasts and early-warning systems conveyed via SMS could help governments and cooperatives anticipate extreme conditions, plan interventions, and distribute support before losses occur.

Climate barometer or bad luck?

Was the 2024 cocoa shortfall simply bad luck—or an early warning of a new normal?

The 2024 harvest in West Africa appears to have combined the worst of both worlds: excessive rainfall and drought in the same growing cycle. This synchronization depressed yields more severely than either extreme alone.

Cocoa’s weather sensitivity is not new, and one major source of year-to-year swings is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, the recurring warming and cooling of the tropical Pacific Ocean.

But climate change is amplifying the intensity of heavy rainfall events as global temperatures rise. The basic physics are straightforward: A warmer atmosphere holds more moisture, amplifying the intensity of rainfall extremes. This brings waterlogging, soil erosion, and conditions that allow for fungal diseases.

Our analysis suggests that rather than being an isolated anomaly, the recent shortfall points to a new normal in a climate-driven shift. Without improved forecasting and adaptation, these climate swings will only deepen the volatility that farmers already face.

Cocoa, in this sense, is more than a crop. It is a climate barometer. The next time you unwrap a Halloween treat, you might remember that the cocoa itself depends on steady rainfall—a balance that climate change might be tipping towards more extreme conditions.

All perspectives expressed in the Harvard Climate Brief are those of the authors and not of Harvard University or the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability. Any errors are the authors’ own. The Harvard Climate Brief is edited by an interdisciplinary team of Harvard faculty.