Harvard Convenes Leaders at a Climate Crossroads

For Jim Stock, Director of the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard University, our current moment is filled with “climate optimism – and deep foreboding.”

The optimism, according to Stock, is well-founded: the stakes and impacts of the climate change are widely accepted; a global youth movement has helped galvanize public opinion; the cost of creating and using clean energy has fallen dramatically; and we have seen significant policy action in recent years.

But, despite this progress, the U.S. is only on track to cut emissions by about one third by mid-century. This trajectory is not good enough to avoid extreme climate impacts and disruption. Getting onto a better emissions path will require a wide range of actors to make very complicated – and sometimes controversial – changes very quickly.

This challenge was the focus of the inaugural Harvard Climate Symposium. On May 9th, more than 500 leaders from across business, government, civil society, and academia gathered on Harvard University’s campus for the symposium. They were joined by over one thousand virtual attendees. This event represented the first of many convenings that will be hosted by the Salata Institute’s Climate Action Accelerator.

In plenary and breakout sessions, leaders and experts discussed some of the most pressing and difficult questions raised by the climate challenge.

What is Our Current Climate Trajectory?

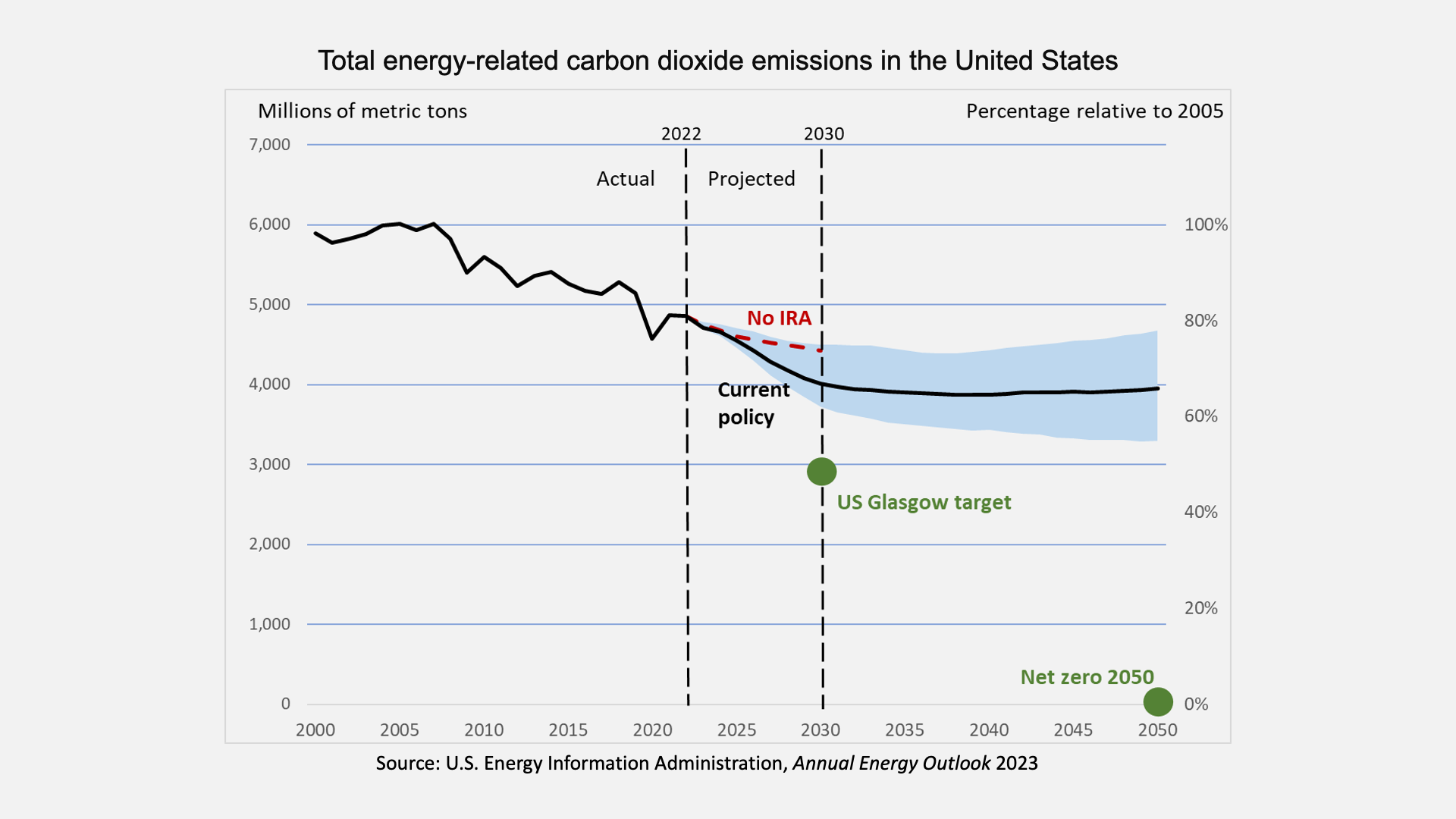

Professor Jim Stock, director of the Salata Institute, framed the symposium by describing the climate path on which we find ourselves today. The economist and first Vice Provost for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard University turned to a chart to illustrate the “glass half full, glass half empty” situation we currently face.

The chart shows current and projected emissions of carbon dioxide from energy in the United States according to a study released in March 2023 by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). The EIA’s projections for U.S. CO2 emissions make clear that the U.S. will not hit its climate targets without significant further action. As Stock noted, there are other, rosier views of our current path – the most optimistic of which estimates that the U.S. will achieve about a 40% emissions reduction relative to 2005 levels by 2030. But no serious analysis suggests that the U.S. is currently on track to hit its emissions reductions goals.

If the rest of the world follows, we will experience disastrous warming.

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate, John Kerry underlined the consequences of this trajectory during a virtual fireside chat with Harvard President Lawrence Bacow. “We’re heading toward 2.5, perhaps 3 degrees. So folks have a real reason to be deeply agitated and concerned about what we’re doing,” said Secretary Kerry. And, as speakers throughout the day noted, the consequences of that level of warming would not be felt equally. “In this country and globally, it is the most vulnerable who will suffer the most,” said Stock.

How Do We Get on a Better Emissions Path?

While the symposium launched with a clear-eyed assessment of our current climate trajectory, there was no lack of energy or optimism as participants explored climate solutions. As Peter Tufano, Baker Foundation Professor at Harvard Business School and Senior Advisor to the Salata Institute, put it: “We’re on a path that’s better than it could have been but not as good as it needs to be – so how do we move to a different path? A better path?”

Plenaries and breakout sessions throughout the day considered the wide range of actions that could be taken by actors in government, business, and civil society to significantly reduce emissions.

Strengthening Global Climate Ambition

“There are 20 nations in the world responsible for 76% or so of all the emissions on the planet,” said Secretary Kerry during the virtual fireside chat with President Bacow. “Those 20 countries have to lead the way in this transition.” Kerry argued that only about half of those 20 nations are taking meaningful action to curb emissions. “The United States, Canada, Japan, Korea, EU, UK — they are actually pursuing real plans to keep the temperature increase to 1.5 degrees,” said Kerry. “The problem is China, Russia, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico, and others are not yet there. And our challenge is to bring them on board as fast as we can.”

President Bacow asked Secretary Kerry about the many factors complicating the clean energy transition for these top-emitting nations.

As many speakers throughout the day acknowledged, recent volatility in energy prices, largely driven by the war in Ukraine, present a real stumbling block for the global clean energy transition. President Bacow asked Secretary Kerry about the tension between nations’ long-term interests in transitioning to clean energy and shorter-term energy security concerns.

“Yes, of course there’s a tension. Enormous tension,” said Kerry. “In the end, we really need to deal with this challenge of energy security in a much more thoughtful and, frankly, fact-based way,” said Kerry. “The truth is that energy security will exist and can exist with massive amounts of renewable power being the centerpiece of your power source.” Kerry highlighted Germany as an example of a major industrial nation that has made the decision to deploy significant renewables and argued that nations should deal with “facts, not scare tactics” in making decisions about energy security and the clean energy transition.

But Kerry acknowledged that very real short-term imperatives, including energy security, are constraining nations’ abilities to transition away from fossil fuels as quickly as is needed. “No one wants to see the economies of the world crash, which is what could happen if you drove the price of oil and gas up too much and drove supply down to too little,” said Kerry. “So we’re in this terrible fix – but we could be transitioning faster than we are. That’s the bottom line.”

The complex U.S.-China relationship presents another challenge for the global clean energy transition. Kerry referred to our relationship with China as “one of the great challenges of our time” and underscored the importance of China’s role in addressing the climate challenge. “30% of all the emissions on the planet are coming from China,” said Kerry. He argued that it was possible and important to separate climate negotiations from other areas of disagreement between the two nations. We can accomplish things together, said Kerry, even as we disagree.

President Bacow also asked Secretary Kerry about tensions between the U.S. and European nations over the “Made-in-America” provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act. “Clearly a number of countries in Europe have been upset by the [Inflation Reduction Act],” said Kerry. “Our principal message to our friends in Europe – and they are friends, obviously – is to do the same thing,” said Kerry. “Go do it!”

Despite these many tensions and complicating factors, Secretary Kerry pointed to ambitious targets already set by many high-emitting nations as cause for optimism. “[The U.S.] target is at 50 to 52%; Europe is at 55%; the UK is at 68% – so people are embracing a very strong goal here.”

And Kerry emphasized the importance of the upcoming COP28 convening in Dubai. “This will be one of the most important COPs that I’ve taken part in,” said Kerry. “If we don’t make this COP successful, there’s no way we hold on to 1.5 degrees.”

Secretary Kerry highlighted that the loss and damage fund created in a breakthrough agreement at COP27 will be a key focus at COP28, arguing that it is important for developed nations to support the fund. “The developed world is responsible for what’s happening in so many places around the planet,” said Kerry. “You can’t have any credibility in this dialogue if you don’t acknowledge that.” But, for Kerry, this is just one side of the issue. “We have a big responsibility,” said Kerry. “But on the other hand, so do other countries, some of whom are not yet fully developed nations but they have big economies – and they could contribute.” “To some degree,” said Kerry, “it will be decided by what the market will bear in the negotiation and the financing.”

Financing the energy transition

“The money is there if we’re serious,” said Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of England and Chair and Head of Transition Investing at Brookfield Asset Management. Carney, participating in a plenary session titled “How Do We Move to a Better Emissions Path?” noted that 40% of the world’s private financial assets have made commitments to manage their financed emissions in line with a 1.5 degree target. The total sum on those balance sheets is over $150 trillion. “That is enough money to finance the energy transition,” said Carney.

But, as Carney pointed out, the financial sector will not act in a vacuum. “Finance is an enabler. It’s a catalyst,” said Carney. “I remember enough of my Harvard chemistry to know that catalysts only work because of the underlying components.” The required components, Carney said, include clear and credible climate policy. “We are on the cusp – but we aren’t there yet,” said Carney.

To spur action quickly within the financial sector, argued Carney, climate transition plans should become mandatory for all financial institutions and major companies. “A few years ago, no banks had [climate transition plans]. Now over 60 banks do,” said Carney. “We need to move from this agreed approach in the private sector, a voluntary approach, to a better mandatory approach in the course of the next couple of years if we’re really serious.”

While Jeremy Grantham, founder of GMO, shared that he was pessimistic about the world’s ability to rise to the climate challenge generally, he expressed optimism about the role that American venture capital could play in driving the innovation needed to address climate change. “The venture capital industry is the biggest and the best and the most dynamic,” said Grantham.

While many other speakers throughout the day shared cautious optimism about the role private finance could play in the clean energy transition, many also pointed out that the private resources available to finance this transition are largely concentrated in the wealthy nations of the global north and in China.

In a breakout session titled “Financing the Energy Transition in the Global South,” Kevin Urama, Acting Chief Economist and Vice President for Economic Governance and Knowledge Management at the African Development Bank Group, pointed to an estimated gap of almost $30 billion U.S. dollars annually needed to finance the clean energy transition on the continent of Africa alone. “The financing gap is huge,” said Urama. And, as Urama argued, the gap stems in large part from systemic issues in the finance sector. “The structure, the flow, and the scale of climate financing is totally misaligned with climate vulnerability and climate risks,” said Urama. A major issue contributing to this misalignment highlighted by Dr. Agnes Kalibata, President of AGRA and former Rwandan Minister of Agriculture and Animal Resources, is financial institutions’ focus on nations’ risk ratings. “We can’t have AAA ratings in an environment where people are dying,” said Dr. Kalibata.

Secretary Kerry and others highlighted the role that blended finance could play in accelerating global investment, including in the global south. “This alliance came together of financial institutions that said we are prepared to put capital on the line – but we need investable, bankable projects. So our challenge has been how do we help create these bankable projects,” said Kerry. Kerry said that the U.S. has been negotiating with countries including South Africa, Vietnam, Indonesia, Mexico, and Brazil, to put together partnerships to find enough concessionary funding to bring the private sector to the table by de-risking the investment. This de-risking, Kerry explained, can be achieved by bringing together multilateral development banks, philanthropy, and the voluntary carbon market to provide sufficient capital to attract investment.

Mark Carney also touched on the promise of the blended finance approach but cautioned that “it’s possible – but there is great need for expertise to work on that design.”

Beyond blended finance, Carney highlighted that international financial institution reform may be able to address these issues. “What is in play, for the first time in my professional career – truly in play – is a fundamental reform of the international financial system,” said Carney. Such reform, according to Carney, could bring in concessional capital to minimize risks and buy down interest rates, driving private investment.

Expanding and Strengthening Corporate Net-Zero Targets

A rapidly growing number of businesses are announcing greenhouse gas emissions reductions targets, including net-zero goals. In a plenary session titled “Net-Zero Commitments: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly,” Professor George Serafeim sat down with Kristen Siemen, GM Chief Sustainability Officer, and David Blood, Founding Partner, Generation Investment to discuss the drivers and impacts of these types of targets.

Professor Serafeim asked Kristen Siemen about how GM landed on their current commitment to become carbon neutral in their global products and operations by 2040 and to eliminate tailpipe emissions from new light-duty U.S. vehicles by 2035.

Siemen responded that GM is a “technical, engineer-based” company and that every goal set by the company has a “path and a trajectory” through which it can be achieved. “In some cases, though, we set a goal that’s realistic but we’re not quite sure how we’re going to achieve that. And in many cases we’ve found that we’re able to go faster than anticipated,” said Siemen.

“Sometimes you just need to start,” said Professor Serafeim.

David Blood highlighted that the most impressive commitments from the perspective of investors are aggressive, achievable, and based on science based targets. “Ultimately, what we’ll hold [companies] accountable to is how ambitious they are relative to their tools and whether they are in fact thinking about it in a holistic way from a company perspective – which means governance, strategy, reporting, setting targets, and risk management. And what we’ll do is insist that the reporting is consistent.”

“It’s not acceptable from our perspective to just say that we agree to be carbon neutral – which is not the same as net zero – by 2050. That to us is not acceptable. Because unless there is a [plan to get there], then we’re really not going to achieve what we want to achieve,” said Blood.

The lack of reliable data and reporting surrounding corporate net-zero targets presents a serious issue for investors, according to Blood. “The data that we’re utilizing to assess whether companies are becoming net-zero is still, frankly, flawed,” said Blood.

Professor Serafeim, who moderated the panel, is part of an interdisciplinary climate research cluster project funded by the Salata Institute working to address the lack of tools for assessing corporate net-zero targets. Read more about the Corporate Net-Zero Targets Project here.

Implementing the Inflation Reduction Act Quickly, Equitably, and Efficiently

“It’s suddenly dominating everything,” said Gillian Tett, chair of the editorial board and editor-at-large, US of the Financial Times, while moderating the first plenary session of the day. Speakers throughout the day remarked on the significant investment and behavior already being driven by the new legislation. “The IRA is one of the most important and exciting pieces of legislation I’ve seen in years,” said John Kerry. “And it’s profoundly important to this moment.”

But, as Richard Newell, CEO of Resources for the Future, put it: “Passing the law isn’t the end of the story.”

“There are a number of very important provisions and how those regulations get written is going to be very impactful in terms of the incentives it provides, not only to deploy technology but to do it in a way that actually reduces emissions,” said Newell.

Mindy Lubber, CEO and President of Ceres, expressed concern about the speed with which the IRA might be implemented. “As a former fed government employee… government doesn’t necessarily move fast enough,” said Lubber. “If we want that $369 billion dollars and the $2.5 trillion – with a T – dollars from the IRA to happen and to make a difference, we need to act now.” Specifically, Lubber highlighted the need for engagement with government to drive quick action, calling for comments on proposed IRS rules, for example. “It will not happen without our engagement,” said Lubber.

Speakers also addressed the imperative for the IRA to be carried out equitably. “We need to ensure that this law – these words on paper – become real-world benefits in people’s lives by addressing the racial inequities, the systemic inequities in the communities that have been bearing the heavy burden of pollution for far too long,” said Vickie Patton, General Counsel for the Environmental Defense Fund.

Complicating the efficient and equitable implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act — and decarbonization in the U.S. generally — is the need to overhaul U.S. energy infrastructure.

“As we pivot from fossil fuel-powered vehicles and heating to electric, demand on the electrical system will likely increase 50-100% over the next 25 to 30 years,” said to Paul Joskow, Elizabeth & James Killian Professor of Economics at MIT, during a breakout session titled “Reforming US Energy Infrastructure Siting to Drive Low-Carbon Electricity.” According to many panelists, meeting that demand in a way that is consistent with the nation’s climate goals will require a massive overhaul of U.S. energy infrastructure – infrastructure that has advanced little since the 20th century, according to panelists, because electricity demand has been stagnant or slightly waning for decades.

The greatest challenge presented by this is overhaul, according to panelists, is the construction of high-power transmission lines between the plants where the energy is generated to where it is used. Central to the challenge of constructing high-power transmission lines is the current debate over permitting. In a nutshell: “It’s hard to get the permission to move electrons from one part of the country to another,” said Secretary Kerry.

Paul Joskow joked that a stakeholder had recently characterized the U.S. energy permitting infrastructure as a “spider-web of entities that all have the power to say no.”

Christopher Knittel, George P. Shultz Professor at MIT Sloan School of Management and director of MIT’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research, referred to recent legislation introduced by Senator Whitehouse aimed at addressing the transmission citing problem as one possible solution. The legislation, according to Knittel, would create a federal authority to decide where transmission lines are built.

Ari Peskoe, Director of the Electricity Law Initiative, Environmental & Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School expressed optimism that the necessary reforms to U.S. energy infrastructure would be accomplished. “I think we’ll do it – but I’m not sure that there is going to be a single unifying policy,” said Peskoe. “One important characteristic of our grid is that it’s local and regional in nature,” said Peskoe. “We’ll have different experiments happening across the country… and ultimately the needs will push through solutions.”

Addressing Regulatory Volatility

Speakers at panels throughout the day emphasized that much of the clean energy transition in the U.S. and globally depends on decision-makers being able to rely on clear and stable climate policies. Many highlighted the complications and uncertainty arising from major climate policy shifts under the Trump administration.

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and Deputy EPA Administrator Janet McCabe both addressed this recent volatility in plenary sessions.

“Regulations, in large part, are about regulatory certainty for industry – and we haven’t had a lot of regulatory certainty for industry,” said Deputy Administrator McCabe. “But that is one of our goals as we move forward.” McCabe highlighted the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law as two landmark pieces of legislation that should provide certainty to decision-makers. “Those things will last,” said McCabe.

Secretary Kerry acknowledged that these shifts can complicate U.S. climate leadership on the global stage but argued that regardless of any change in the U.S. presidency, “there’s no way we’re going backward.” Secretary Kerry pointed to private sector commitments from companies including Ford, GM, Google, and Apple, and argued that “the global economy has made this decision, and it’s more powerful than any politician.”

Deputy Administrator McCabe also argued that, despite recent volatility, “the motor keeps running,” crediting fundamental laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. “We have these fundamental laws that were adopted in bipartisan fashion decades ago that require government to keep moving forward to address the changing issues that are in front of us.”

McCabe also called attention to the regulatory agenda being proposed and carried out under the Biden Administration. “We have proposals out for the oil and gas sector, following up on rules that were put out during the Obama Administration to control emissions of methane,” said McCabe. “We have the most aggressive rules ever out on light, medium, and heavy-duty vehicles, that will push this country towards a nearly zero-emission transportation fleet… We are on the brink – literally the brink – of putting out a proposal to address fossil-fired electricity generation.” In the days following the symposium, the EPA released the new proposed power generation rules referenced by McCabe. (Read the Harvard Energy & Environmental Law Program’s quick take on the new proposed rules here).

Adapting to Climate Impacts

Equally important to the task of reducing greenhouse gas emissions is that of adapting to increasingly severe and unequal climate impacts. A breakout session titled “Heat Stress: Science and Solutions” explored one of the most significant global climate adaptation challenges.

“By 2100, heat stroke could kill more people than all infectious diseases combined,” said Francesca Dominici, Clarence James Gamble Professor of Biostatistics, Population and Data Science at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. As Dr. Gaurab Basu, Physician and founding co-director of the CHA Center for Health Equity Education and Advocacy (CHEEA), pointed out, these impacts fall disproportionately on marginalized and underserved communities, domestically and internationally. In the U.S., “redlined communities are 2.6 degrees Celsius hotter than non-redlined-communities,” said Dr. Basu.

Several speakers throughout the day noted that the impacts of heat stress in the global south are already being felt deeply. “Last month in the India’s financial Capital, Mumbai, 13 people died and more than 500 people were hospitalized out of sun stroke in an open air award event last week,” said Ajmal Khan A T, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute at Harvard University during a breakout session titled “Language and Ethics of Climate Change.”

Panelists considered solutions ranging from tree canopies, heat pumps, and heat alerts to cooling centers. Several highlighted the need for careful planning and stakeholder engagement in implementing any heat stress solution. “One example is cooling centers – we can build them, but if people don’t come they’re not going to do any good,” said Lisa Robinson, Senior Research Scientist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “We really need to be thinking really carefully about how we design these centers, where we locate them, what sorts of additional services we need – do we need transportation, do we need to have a big public information campaign – in order for those solutions to be really effective.”

Panelists cited new initiatives underway across Harvard University aimed at addressing climate impacts, including heat stress. Kari Nadeau, Chair of the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, announced during the breakout session on Heat Stress that Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Boston University School of Public Health were awarded a $6.7 million, three-year grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences to create a Research Coordinating Center (RCC) on climate change and health. Francesca Dominici said that the goal of the new center is to “coordinate research activity among individual researchers and research teams, to facilitate data exchange and best practices in analyzing data, and to provide opportunities to build capacity in conducting research on climate change and health.”

Two interdisciplinary climate research clusters launched by the Salata Institute in February seek to advance climate adaptation research and implementation in South Asia and the Gulf of Guinea.

Civil Society in Action

In a plenary session titled “What Can I Do?” moderated by Marshall Ganz, Rita E. Hauser Senior Lecturer in Leadership, Organizing, and Civil Society at the Harvard Kennedy School, panelists discussed the role individuals and civil society can play in driving climate solutions.

“In my experience and background, it seems like major change in policy seems to usually come as part of some profound disruption. Maybe a war, maybe a depression – but more hopefully a social movement,” said Ganz. “Where do you think the urgency [for climate action] is going to come from?”

Panelists Roxanne Brown, International Vice President at Large of the United Steelworkers, and Sam Sankar, Senior Vice President for Programs at Earthjustice, highlighted that in many communities this urgency already exists, driven by climate impacts and disproportionate pollution.

“There’s a real common misunderstanding that climate change concerns are the concerns of wealthy, well-to-do, largely White suburban audiences,” said Sankar. “If you do polling in this country, you will see that Black and brown communities are more concerned about climate change, more concerned about environmental issues, in general. And that is because they’re living them.”

Roxanne Brown said that there is a deep feeling of urgency for climate action among the industrial workers represented by United Steelworkers. “There’s this disconnect that people often have about industrial workers – oil workers in particular – and about whether or not they care about climate change,” said Brown. “They care about climate change. Our members in the Gulf can tell you what happened to their refineries during these super storms we experienced over a period of years.” Their plants and livelihoods are constantly being impacted by climate change, argued Brown.

Panelist Brad Campbell, President of the Conservation Law Foundation, addressed the need to translate the urgency felt in communities to urgency on the part of the fossil fuel industry. “I think the urgency is ultimately going to have to come from people connecting [impacts] to the fossil fuel industry and holding them accountable,” said Campbell. “Civic engagement in New England has left us with five out of six states that have strong emissions reduction mandates.”

Panelists agreed that, despite significant support for climate action, many issues complicate civil society’s role in driving that action effectively.

Policy solutions to climate have historically left front line communities behind, argued Campbell, leading to a lack of trust between decision-makers and the communities disproportionately experiencing climate impacts and pollution. Brown highlighted that this lack of trust is shared by workers who stand to lose out as the clean energy transition reshapes the global economy.

“For some in the labor community, the phrase, ‘just transition’ – and every conversation around climate has included this phrase – some people describe that as a ‘fancy funeral,’” said Brown, arguing that United Steelworkers members in industries ranging from rubber to chemicals and oil and gas, stand to lose high-paying jobs. “Where we have a lot of frustration is that in the jobs my members have right now… pay a sustaining family wage. The jobs in clean tech aren’t there yet,” said Brown. “We want environmental sustainability – it’s necessary – but workers deserve economic sustainability.”

Despite these challenges, panelists found reason for optimism.

Sam Sankar pointed to significant progress in the public conversation around climate, highlighting that climate denial is no longer a viable strategy for mainstream leaders and decision-makers. Sankar also pointed out the central role that front line communities can play in climate solutions. “The most powerful movements that we’ve seen… are community groups dealing with the day-to-day impacts of the fossil fuel industry,” said Sankar.

Brad Campbell pointed to the high degree of engagement of Gen Z as another reason for optimism. “Gen Z is going to the polls and climate is a motivating factor,” said Campbell. “There is urgency with that generation.”

For Roxanne Brown, the path to turning urgency into action lies in coalitions. “Today, when people are approaching organizing, they’re coming up with community tables… They’re pulling in Black and brown members of the community; they’re pulling in the environmental community; they’re pulling in women’s groups; they’re pulling in local colleges and universities,” said Brown.

Dig Deeper

The conversations outlined here represent just some of the many that took place at the Harvard Climate Symposium. Dozens of speakers participating in plenaries and breakout sessions throughout the day provided deep expertise on a wide range of climate and sustainability topics.

Experts including Peter Huybers, Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University, John Holdren, Research Professor at the Harvard Kennedy School, Dan Schrag, Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and Professor of Environmental Science & Engineering at Harvard University, and Zhiming Kuang, Gordon McKay Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Science at Harvard University presented a breakout session titled “Climate Science: What is Settled, What is Not?”

Cajetan Iheka, Professor of English at Yale University and Karen Thornber, Harry Tuchman Levin Professor in Literature and Professor of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University, led a breakout session titled “Language and Ethics of Climate Change.” This breakout session brought together Joni Adamson, President’s Professor of Environmental Humanities at Arizona State University, Stephen Gardiner, Professor of Philosophy and Ben Rabinowitz Professor of the Human Dimensions of the Environment at University of Washington, Seattle, Ajmal Khan A T, Postdoctoral Fellow at the South Asia Institute at Harvard University, and Meg Parsons, Associate Professor at University of Aukland.

A breakout session titled “Trade, Onshoring, and International Climate Policy Tensions Among Allies brought together experts including Joseph Aldy, Professor of the Practice of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, Nat Keohane: President of C2ES, Catherine Wolfram: Visiting Raymond Plank Professor at the Harvard Kennedy School, and Mark Wu, Henry L. Stimson Professor of Law, Harvard Law School.

Meghan O’Sullivan, Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at the Harvard Kennedy School, moderated a breakout session titled “International Security, Energy Security, and the Energy Transition,” guiding a discussion between Joseph Aldy of the Harvard Kennedy School, Kelly Gallagher, Academic Dean and Professor of Energy and Environmental Policy at Tufts University, and David Goldwyn, President of Goldwyn Global Strategies.

A breakout session titled “Climate Entrepreneurship and Carbon Removal” moderated by Peter Tufano, Baker Foundation Professor at Harvard Business School and Senior Advisor to the Salata Institute, explored developments in the Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) space. Tufano was joined by Noah Deich, Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Office of Carbon Management in the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management, Laura Lammers, Founder and CEO of Travertine Technologies, Inc., Marty Odlin, Founder and CEO of Running Tide, and Ramsay Ravenel, President & CIO of the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment.

“Future Innovation and Acceleration Leaders,” a breakout session moderated by Karan Takhar, Dual MPP-MBA Candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School and Wharton Business School, brought together Jenny Datoo, Senior Knowledge Management Officer for the Climate Change Group at the World Bank, Shari Friedman, Managing Director for Climate and Sustainability at Eurasia Group, Elizabeth Lewis, Managing Director and Deputy Head of ESG at Blackstone, and Jonah Wagner, Chief Strategist at the U.S. Department of Energy Loan Programs Office.

What is Next?

In remarks welcoming symposium participants to the Harvard Business School campus, Dean Srikant Datar of Harvard Business School underscored the importance of convenings like this one. “I am delighted at the prospect of face-to-face exchange of ideas and information that will occur today and in the coming days to accelerate and amplify action across disciplines, across functions, and across organizations,” said Dean Datar.

This inaugural Harvard Climate Symposium was the first of many such events that will be hosted by the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability.

In addition to bringing stakeholders together, the Salata Institute is also leveraging Harvard’s many areas of expertise to find practical solutions to the challenges raised during the symposium. Five new interdisciplinary climate research clusters are exploring ways to reduce global methane emissions; advance climate adaptation research and implementation in South Asia; strengthen and expand corporate net-zero pledges; advance climate adaptation and build local resilience capacity in the Gulf of Guinea; and help communities in the U.S. navigate the energy transition equitably and efficiently. A new seed funding program launched by the Institute in April will grant awards of up to $30,000 to fund early-stage and interdisciplinary collaboration on understudied and emerging topics in climate change and sustainability. This month, the Salata Institute and the Harvard Office for Technology Development announced a translational fund to propel climate and sustainability-related innovations towards startup formation for global impact.

To stay up to date on future events and the Salata Institute’s work, follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram.