Unpacking Trump’s EV policy overhaul

President Trump declared his intention to reverse the Biden administration’s electric vehicle policies in his Inauguration Day executive order, “Unleashing American Energy.” It remains to be seen which policy changes will become final, as changing laws passed by Congress will require Congressional action and revoking regulations takes time.

But we can model what potential changes under Trump mean for EV sales, for emissions, and for federal government spending.

First, some important considerations: Every new EV sold means fewer carbon emissions than if the same driver were behind the wheel of an average gasoline-powered – or internal combustion engine (ICE) – vehicle, and that gap will increase as the grid decarbonizes. EV sales domestically also support the U.S. auto industry’s ability to compete in the global transition away from ICE vehicles and toward EVs. The U.S. market already lags the EV transition in China and Europe, but would lag even further without Biden-era laws that support EV adoption and the development of a domestic EV battery industry. The fiscal impact – reducing spending or increasing tax revenues – is important because some Republican leaders are looking at EV programs as a source of budget savings that can be redirected to their policy priorities.

In a recent policy brief, we looked at a menu of eight scenarios under discussion in Washington. We model drivers’ vehicle purchase choice and EV charging-station buildout – two things supported by the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (the IIJA, also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Specifically, we estimate the share of battery electric vehicle sales each year.

One policy, big impact

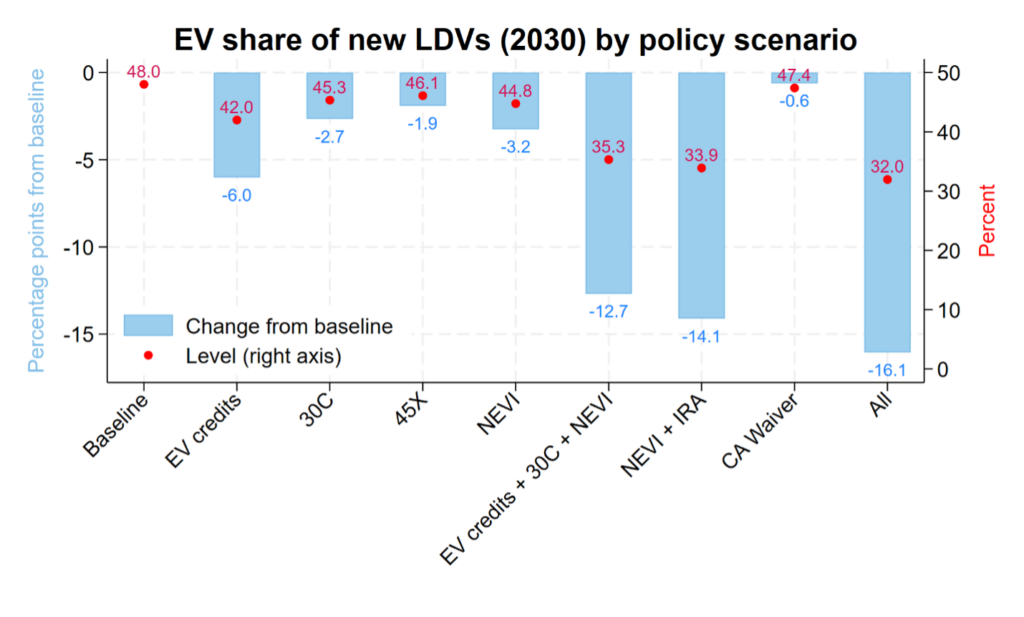

The single policy change with the largest effect – reducing EV adoption and driving up carbon emissions more than anything else – is removing the IRA’s EV tax credits for new, used, and commercial EV purchases. Eliminating the credits makes it more expensive for an American to buy an EV. That means fewer EV sales – 42% of the total new cars sold in 2030 compared to 48% if the current law stands (see the red dots in the chart below).

Then there are emissions: Removing the EV credits would increase 2030 emissions from light-duty vehicles by 20 million metric tons (mmt) in 2030 compared with the current law baseline of 1,040 mmt. (Given that a new vehicle sold today is expected to be on the road for 15-20 years, this 20 mmt of emission reductions in 2030 translates into at least 10 times the emission reductions over the lifetime of the vehicles.)

The budget impact is also by far the largest of any single policy change we model: Removing the IRA EV tax credits for new, used, and commercial EV purchases offers the federal government $169 billion in savings over the 2026-35 budget window.

Other scenarios

A relatively small amount of IIJA and IRA funding goes to charging, but because of the importance of charging to EV adoption, eliminating that funding would have an outsize impact on EV sales. Just terminating the $5 billion National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program (part of the IIJA) would cut the EV share of new vehicle sales by 3 percentage points (pp), while generating fiscal savings of only $12 billion, including the tax credits not provided because of reduced EV sales. The NEVI program was designed to enable any EV driver to make a road trip on major Interstates, by placing at least four fast chargers every 50 miles along those highways. Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy has already ordered states to freeze NEVI spending.

Repealing the IRA battery and critical mineral production tax credits would reduce 2030 EV sales by 2 pp and cut fiscal costs by $7 billion. These credits may have stronger political support in Congress than other IRA and IIJA EV provisions because 83% of battery investments are in districts represented by Republicans, according to Jay Turner at Wellesley College.

Eliminating all IRA and IIJA support for EVs would slash the EV share of new vehicle sales by 14 pp in exchange for $173 billion in 10-year federal budget savings. Because these programs reinforce each other – more charging infrastructure begets higher EV sales and vice versa – the effect on sales and emissions of eliminating all of them exceeds the sum of their parts.

The most extreme scenario is eliminating all support for EVs under both the IRA and IIJA, plus withdrawing California’s waiver under the Clean Air Act. The waiver allows California to set tougher emissions standards – and corresponding requirements for the zero-emissions share of new vehicles – reflecting authority granted to California in the 1970 Clean Air Act and used hundreds of times by Republican and Democrat governors over the past 50 years. It also enables other states to follow California’s tougher standards; 11 other states plus Washington, D.C., have joined California in committing that 100% of new light-duty vehicles sold in their states will be zero-emissions by 2035. If California’s waiver and those states’ 2035 zero-emission goals were eliminated, along with all the IRA and IIJA support, the 2030 EV share of sales would drop by 16 pp to 32% and emissions increase by 44 mmt. Yet the federal budget savings would be little different from just eliminating the EV tax credits, at $173 billion.

An important takeaway: Cutting federal policy support for EV adoption will slow, but not stall, growth in EV sales. We estimate that even the most extreme scenario of removing all the policies we model would still see EV sales climb to 32% in 2030, four times the 8% they were in 2024 according to Cox Automotive. As battery costs continue to come down, EV prices will fall. EVs are on track to be less expensive than ICE vehicles later this decade.

Bottom line

Withdrawing any of the federal policies supporting EV adoption will slow EV sales in the coming years, compared to the outlook under current law. Even without these supports, EV adoption will rise as EVs become less expensive than gas-powered vehicles thanks to falling battery costs, larger ranges, and more mainstream battery electric models available to consumers, and as the private sector and states build out charging stations. Years of slower EV sales growth, however, will translate to fewer EVs on the road over the next decade, more carbon emissions accumulating in the atmosphere, and U.S. automakers falling farther behind in the global race for market share in the EV future.

All perspectives expressed in the Harvard Climate Brief are those of the authors and not of Harvard University or the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability. Any errors are the authors’ own. The Harvard Climate Brief is edited by an interdisciplinary team of Harvard faculty.