Harvard COP29 attendees reflect

Harvard students and faculty who attended the annual United Nations climate negotiations described their experiences before a packed hall inside Harvard Kennedy School on December 9. This year the Conference of the Parties, COP29, was held in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan.

The UN treaty that oversees the COP meetings is unique because it brings official negotiators from around the world together with civil society actors, said Robert Stavins, A.J. Meyer Professor of Energy & Economic Development and director of the Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, speaking of his seventeenth COP. Over the years, Stavins has seen the emphasis at COP shift decisively toward civil society.

“When I first went to the COP in Bali 17 years ago, 80% or 90% of the meaningful action was the negotiations among the official government delegations,” Stavins explained. Now, “I’d say that 85 to 90% of the meaningful action is in the periphery, the environmental NGOs, trade associations, universities. That’s become the main event.”

That has expanded opportunities for students. The Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability at Harvard this year supported 11 students traveling to Baku.

“There is definitely a side show, and I am most certainly part of that,” said Angela Zhong, a Harvard College senior studying Economics and Environmental Science and Public Policy, sharing impressions from her fourth COP. “By being at COP, you’re able to meet with a lot of high-level negotiators who, I think, would not give me the time of day otherwise. Because that is the one opportunity and window where you can push and remind them why they’re there and why we’re all trying to do all this good work.”

Adarsh Kumar, a dual-degree student at Harvard Kennedy School and MIT Sloan School of Business attending his first COP, enthused about meeting people working in his focus area, food security.

He described holding a “phenomenal number of conversations with negotiators, from ministers and from folks in the periphery, from multilateral development banks and private organizations about the importance of food systems, both in the mitigation context, but increasingly more and more in the adaptation context, with new climate realities sort of sinking in. How do we ensure that yields are still robust so that we can feed our people?”

Other students who traveled to Baku shared their reflections in writings, which we excerpt below.

Jerry Huang, Harvard College (Computer Science)

One of the most rewarding aspects of COP29 was the opportunity to present the Green AI Institute’s research alongside Deputy Secretary-General of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), Tomas Lamanauskas. Our work on the Green AI Index, which provides a framework for assessing the environmental impacts of AI technologies, resonated with attendees and sparked meaningful discussions about the need for global standards in sustainable AI.

Isabel Kelly, Harvard Kennedy School

The risk of COP29 ending with no agreement was high, but countries ultimately signed up to a $300 billion climate finance target by 2035, and a looser commitment to “secure efforts of all actors to work together” to scale this up to $1.3 trillion. … Despite this, COP29 demonstrated the private sector and civil society’s immense determination to scale up climate finance. This movement has huge momentum and is not dependent on a negotiated figure in the text of a COP agreement.

Donguk Lee, Harvard Graduate School of Design

I realized the indispensable role of local governments in achieving the Net Zero emission goal by 2050. … local governments are uniquely positioned to implement actionable climate strategies. They act as the crucial bridge between national policies and community-level implementation, translating broad climate targets into tangible outcomes. Local leaders play a key role in addressing the specific needs of their communities while fostering public-private partnerships and mobilizing local resources to drive climate action.

Eli Lichtman, Harvard Business School

I ventured into the negotiations to watch delegations debate the minutiae of specific language and verbiage choices that have long-lasting impacts. Although it sounds trivial, the power of words was evident. … It was fascinating to listen to the group pore over line after line, agonizing over each word. How does its meaning change if there is an extra comma? What does it mean to a native English speaker versus a non-native speaker? In the future, is there a way for this clause to be interpreted as multiple parties of the same nationality or multiple, separate parties?

Luca Mantovani, Harvard Business School

It was fascinating to see how much weight a single word could carry and how the language used in agreements reflects different levels of accountability and expectation. … It’s a constant game of strategy and compromise, where representatives are trying to balance their national interests while moving the needle on global climate action. It was a real insight into how complex and delicate multilateral agreements are—and how hard it is to get everyone on the same page.

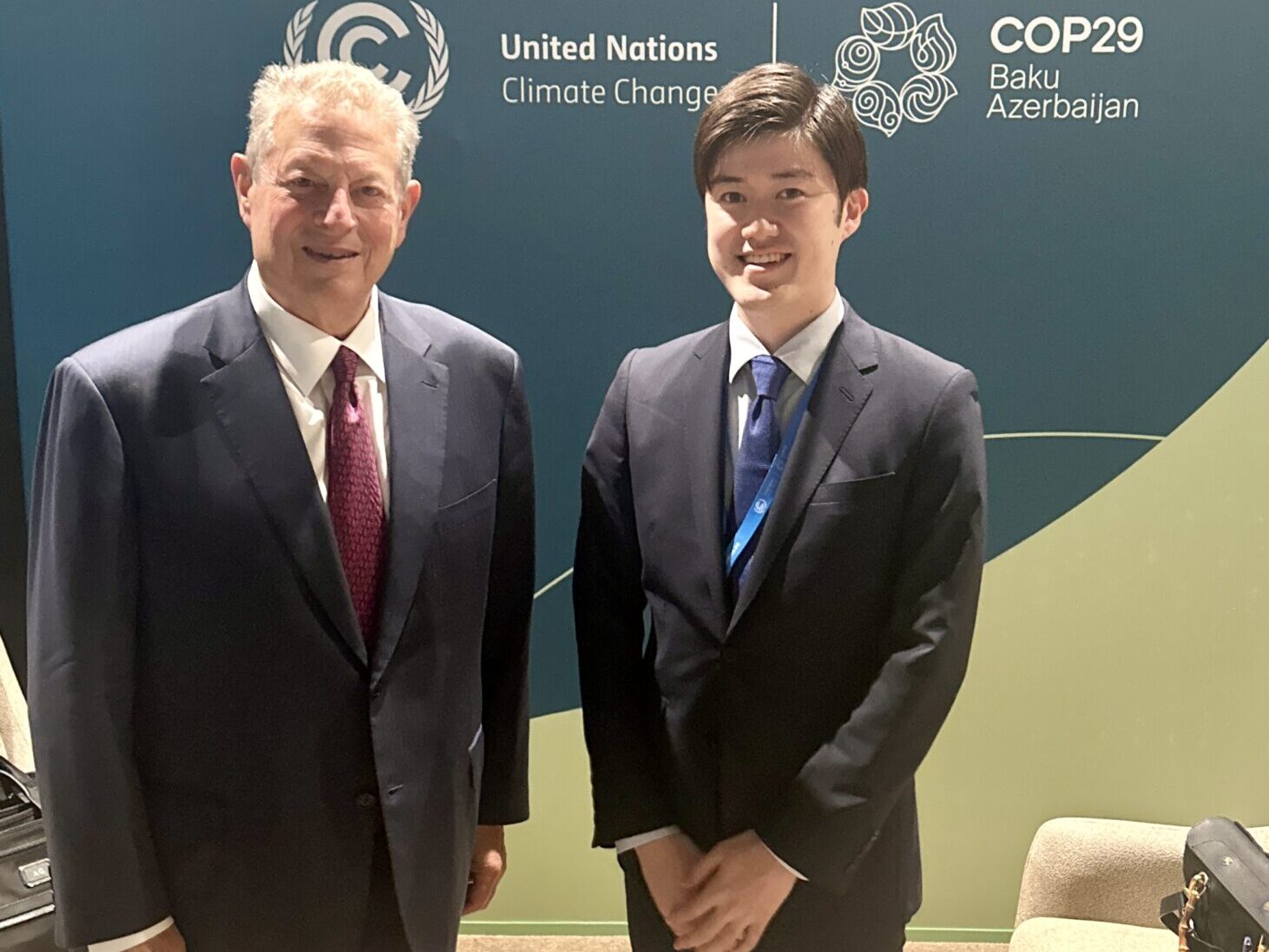

Tomoki Matsuno, Harvard College (Environmental Science and Public Policy)

My discussion with Vice President Gore focused on Climate TRACE, the emissions tracking platform that seeks to provide real-time data on CO2 emissions, which could significantly enhance transparency and accountability in climate action. Our conversation also touched on the political dynamics of climate policy in the U.S., particularly in light of the U.S. presidential election outcome. Mr. Gore’s optimism regarding the continuation of climate initiatives like the Inflation Reduction Act under a second Trump administration was striking, especially when juxtaposed with the less enthusiastic display by the U.S. officials at the U.S. pavilion, which reflected the broader political uncertainty.

Ian Nacarella, Harvard Business School

One of the most surprising aspects of the conference was the prominent presence of oil and gas companies in the Blue Zone. Coming from a climate technology background and aspiring to launch a venture in the space, I found these interactions both intriguing and dissonant. National oil and gas companies presented their narratives on decarbonization and energy transition, often emphasizing their roles in scaling carbon capture, hydrogen, and other emerging technologies. While skepticism about their motives is warranted, I recognized the value in engaging with these stakeholders to understand their perspectives and explore potential opportunities for collaboration. After all, addressing climate change will require significant buy-in and action from sectors traditionally seen as part of the problem.

Grace Taylor, Harvard College (Environmental Science)

What struck me most at COP29 were the stories of individuals and communities who have already been directly impacted by climate change, yet continue to show up, determined to ensure their voices are heard. I listened to accounts from Congolese villagers who have lost their land due to exploitation, facing unprecedented droughts that threaten their livelihoods and futures. I met a Guinean woman who shared how the Ebola outbreak devastated her community, causing schools and hospitals to close. Yet despite these immense hardships, these villagers made their way to COP29 – many for the first time – traveling to a conference where they didn’t speak the language, crossing borders and cultures, simply to have their voices heard. …. They reminded me that fighting climate change is not a matter of abstract policy; it is about real people, with real struggles, fighting for their futures.