Germany’s battery boom reframes the energy transition

Germans have embraced home battery storage with surprising speed.

Between 2018 and 2020, early adopters were willing to pay for batteries years before the technology made financial sense, prioritizing sustainability and independence from the grid even when such systems were expensive and the grid was reliable. Since then, as the economics have improved, the number of homes with storage has grown more than tenfold to over 2 million.

In a forthcoming paper, my colleague Serguei Netessine and I examine what motivated those early adopters – and why this now-profitable trend should worry utilities. The patterns we find offer clues about how quickly other green technologies, such as electric vehicles and heat pumps, may spread in Germany and around the world.

Nonmarket valuation as a driver of adoption

For most early-adopter households, residential storage was not only about financial optimization. To explain why hundreds of thousands of households invested in batteries when the cost often exceeded their potential bill savings, we focus on what we call “nonmarket valuation”: the extra benefit some households perceive from using their own solar power rather than buying electricity from the grid.

Leveraging detailed data on household solar generation, consumption, and capacities, we built a structural model that combines electricity usage patterns and investment decisions to estimate the nonmarket valuation for each household. The median early adopter household in our data values it at 29 cents per kilowatt-hour, we found – roughly comparable to the retail price of electricity itself. In other words, many households valued consuming self-generated solar about as much as they valued the money they could save.

We show that willingness to pay for sustainability and for grid independence drives this nonmarket valuation and leads these households to adopt storage years before conventional break-even models would predict. This is a crucial insight for tech companies and policymakers: The diffusion of green technologies may depend not only on subsidies or savings, but also on intrinsic consumer values. Where climate regulation is stalling, tapping into these preferences offers another way to accelerate adoption.

Since 2020, the installation economics have shifted significantly. Battery costs have dropped by around 25 percent, and electricity prices in Germany have risen by roughly 35 percent. As a result, storage is now financially attractive for an estimated 54 percent of German households, even without accounting for nonmarket valuation or subsidies. While this economic shift explains much of the current growth in Germany, adoption in other markets with lower electricity prices may still depend on other factors. In the United States, for example, the grid can be unreliable. That leads people to purchase batteries as a backup.

A headache for utilities

We show that solar-plus-battery homes buy about 38 percent less electricity from the grid throughout the year. Worse for utilities, these “prosumers” (households that both produce and consume energy) create a challenging demand profile.

Batteries can smooth daily fluctuations, but they cannot solve seasonality. In summer, a battery-equipped home almost disappears from the grid – it runs on long hours of solar generation and uses the battery at night. In winter, however, consecutive dark days with little solar production deplete storage and push the same household back onto the grid.

The utility, as supplier of last resort, must still maintain infrastructure to serve all customers during these winter peaks, but it loses the summer revenue that used to help pay for that capacity. This combination of lower sales and more pronounced variability undermines traditional rate designs and may push utilities toward tariffs based more on fixed connection fees or peak charges than on kilowatt-hours consumed.

The environmental paradox

Adding a battery to rooftop solar is widely assumed to reduce emissions by changing when and how the clean power is used, storing daytime generation and releasing it in the evening when demand is higher. Yet, based on the German data from 2018-2020, households with batteries tended to use more electricity overall.

We call this “storage rebound.” Once a household has a battery, discharging self-generated power becomes cheaper than buying from the grid. That encourages higher electricity consumption. At the same time, less solar is sold back to the grid to displace fossil-fuel generation. The net effect is higher emissions.

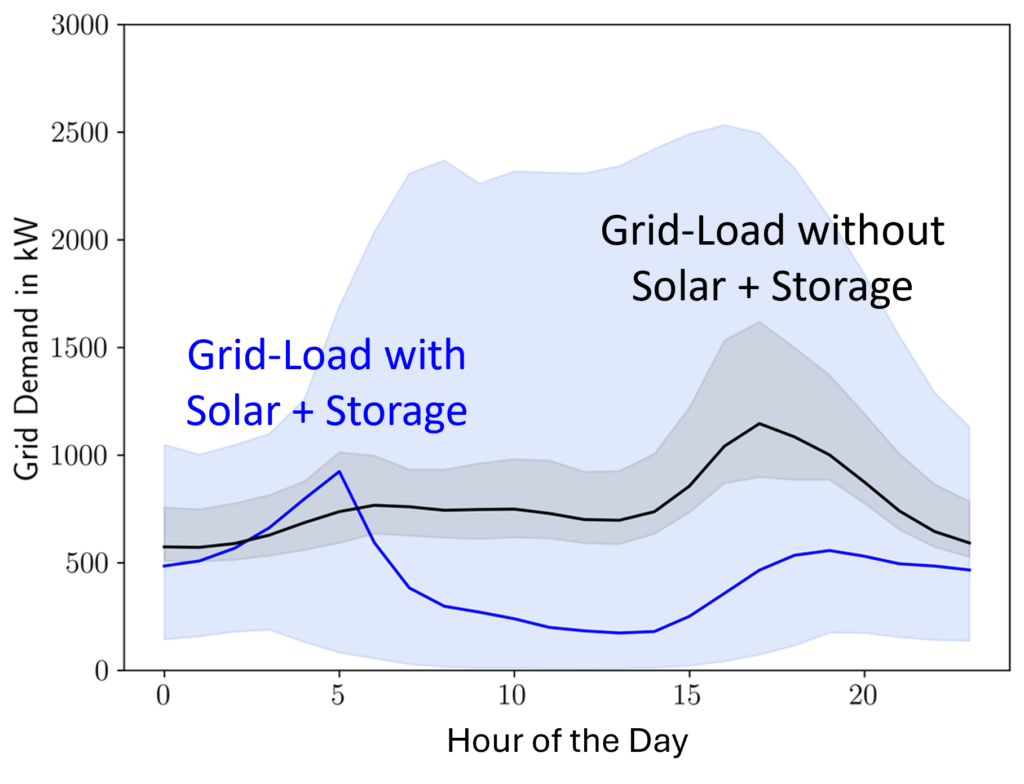

The black line in the figure below shows the electricity that a household without solar or storage buys from the grid on an average day; the blue line shows a household with solar and storage. The shaded areas show how much the demand varies throughout the year for both households. For households with solar and storage, the average purchase is much lower, but the variability much higher.

This is not a verdict on storage as a technology, but a reminder that the energy transition is an evolving process. The impact of a technology depends on timing and on the rest of the system.

As solar penetration rises globally, the dynamics on the grid change: When the sun is high, there may be too much solar generation; when it’s dark, not enough. Batteries can soak up power at midday that would otherwise be curtailed (read: wasted) and release it later to displace evening gas-fired generation. In a grid highly dependent on an intermittent renewable like solar, only storage can provide that shift at scale and help utilize all renewable generation.

Batteries may have increased emissions five years ago, but they are likely to become essential for emissions reduction in the grids of the future.

All perspectives expressed in the Harvard Climate Brief are those of the authors and not of Harvard University or the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability. Any errors are the authors’ own. The Harvard Climate Brief is edited by an interdisciplinary team of Harvard faculty.