Benjamin Franklin was America’s first climate scientist

When I tell people I’ve been writing a book on the Franklin stove, nine times out of ten, they know what I’m talking about or, if I have to explain it, they quickly grasp that the stove is yet another instance of the famous American founder’s fabled ingenuity. But when I explain to people (if they’re still listening) that Benjamin Franklin invented his stoves to combat climate change, questions ensue. Climate, really? Real climate change? Like ours?

Well, yes—if with some differences.

Franklin lived during what’s now called the Little Ice Age (LIA), a period of natural cooling, the opposite of our human-generated heating, but quite similar in its societal impact. The LIA lasted from roughly 1300 to 1850, with sometimes fatal consequences. Major harbors (London, Venice, Boston, Philadelphia . . .) sometimes froze over, paralyzing travel and trade in this age of sail. The particularly bad winter of 1740-41 caused famine in Europe; 13-20 percent of the population of Ireland died, a greater toll than during the nineteenth-century Great Hunger. This was the winter when Franklin experimented with his family’s fireplace to build his first stove prototype, with the goal of generating more heat with less fuel, conservation combined with better living.

Along the way, Franklin became a climate scientist, America’s first, an architect of the emerging field of modern climate science. It’s significant that he was American, because the Americas were a productive source of questions about climate. Ancient geographers had defined climate as a synonym for latitude, a thermally distinct band spanning the globe. But, as it turned out, the Americas didn’t match their European latitudinal counterparts—New England is parallel to Spain and Italy but (still) can’t produce Mediterranean wine and olives. The mismatch was a first hint that climate is complex. Then the extreme weather events of LIA, contrasting with an earlier period of warmth, fostered a sense that climate’s patterns were both complicated and changing, defying easy prediction.

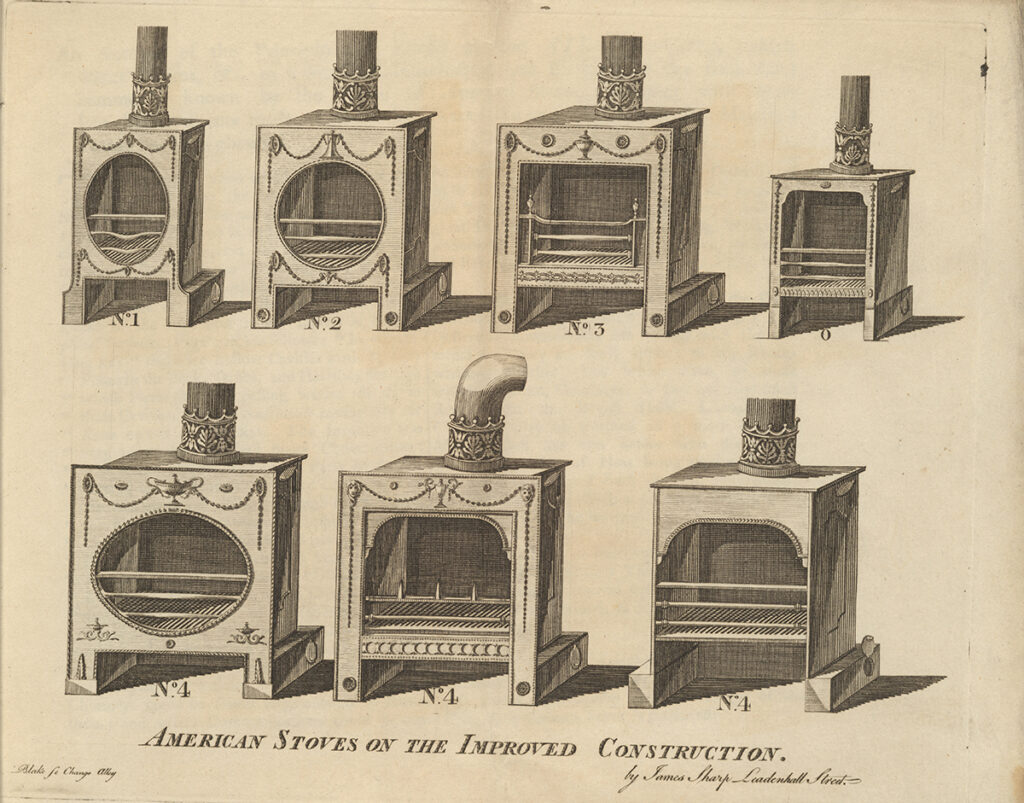

And yet a science of analyzing climate as a complex system of mutable forces was exactly what emerged in Franklin’s era. When he printed a pamphlet to describe his first stoves, Franklin emphasized his experiments into convection, the tendency of heated air to expand and rise, which, properly manipulated, produced an entirely warmed room. This was Franklin’s true invention, not the heater itself, but the artificial atmosphere it created indoors. And from his house-bound observations, Franklin had a way to explain the big atmosphere outside. He used convection to explain Atlantic storm systems, the Gulf Stream, and the spread of volcanic effluvia across oceans and continents, with its likely cooling effect on climate. Meanwhile, he worried that emissions from indoor heating affected the outdoor atmosphere. In the later versions of his stoves, he tried to reburn smoke, recognizing it as a suspension of unburnt particles of fuel, inefficient and a source of air pollution; a friend teased him for being a “universal Smoke Doctor.” He described microclimates in cities, where humans might be heating things up, but urban trees could cool things back down.

Franklin was big on those climate-adjusting trees, so much so that he dissented from the ongoing plan, among his settler contemporaries, to warm up North America by deforesting it. Thomas Jefferson endorsed that hypothesis. But Franklin worried: “Whether enough of the Country is yet cleared to produce any sensible Effect, may yet be a Question,” unanswerable without possibly doing irreparable damage. Settlers might overshoot the mark, making things far too hot, or else leave posterity with less wood to burn in conditions that stayed stubbornly cold. In his doubts, Franklin echoed suspicion that human error might have planetary consequences. Theologians and geologists debated whether Noah’s flood, in shifting vast quantities of water from the earth’s interior to its surface, had changed the planet’s tilt toward the sun, resulting in climatic instabilities, including the Little Ice Age. Human sin did it.

Franklin’s concern for trees, as shapers of climate and as conservable fuel, also registered the work of other scientific observers, some of them close friends: Stephen Hales on plant transpiration, Joseph Priestley on the chemical composition of the air—especially the roles of carbon dioxide and oxygen (as they’d be called) in sustaining life—and Jan Ingenousz on the process later called photosynthesis.

So, most of the pieces of the puzzle that is climate were in place: arguments about mitigation versus adaptation, the chemistry of the atmosphere, human impact on the climate, and so on. Really, the only missing piece was carbon dioxide’s role in warming the atmosphere: Franklin died in 1790; Eunice Foote published her historic experiments with coal gas in 1856.

We’ve taken even longer to put all the pieces together. Much of the but-not-real-climate-really, reaction to my project is, I think, unwillingness to admit that we’re not the first people in history to recognize and fight climate change. We deserve no such merit badge. In fact, what seems most different between Franklin’s then and our now is willingness to discuss the problem openly. Franklin addressed the conditions of the Little Ice Age in his Pennsylvania Gazette, his famous Poor Richard almanac, and his scientific writings. His correspondence shows that both scientific experts and ordinary people pondered the problem. And in his stove-warmed artificial atmospheres (his parlors in Philadelphia, London, Paris), he and many others chatted away about fuel conservation, chimney design, bad winters, living within a set of nested atmospheres—not a denialist or foot-dragger among them.

Joyce E. Chaplin’s new book, The Franklin Stove: An Unintended American Revolution, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux on March 11.

All perspectives expressed in the Harvard Climate Brief are those of the authors and not of Harvard University or the Salata Institute for Climate and Sustainability. Any errors are the authors’ own. The Harvard Climate Brief is edited by an interdisciplinary team of Harvard faculty.